The Council have stated at various times during this dispute, both verbally and in writing, that the residential use of my bungalow had been abandoned. However, there is indisputable evidence to prove that the residential use had NEVER been abandoned.

In fact, the Council’s own chief solicitor acknowledged, in writing, that the residential use had NOT been abandoned prior to these statements being made.

It is not disputed that my bungalow had been in existence for some 56 years at the time I purchased it in 1984, a considerable time and well before the 1st July 1948 (the “Appointed Day” for the Town and Country Planning Act 1947). Given the length of time the bungalow had stood (since 1928) and the fact that the Council were approvingly aware of it, the dwelling would be considered as permanent and entitled.

During any intermittent short period of time when the owner was away, there was no other intervening use other than residential and any absence by the owner was merely temporary. It has been Held in the High Court that if a cessation of use is merely temporary then it does not amount to abandonment and the previous use can be resumed without planning permission.

Throughout any short period that the bungalow may have been empty, it continued to be rated as a residential dwelling.

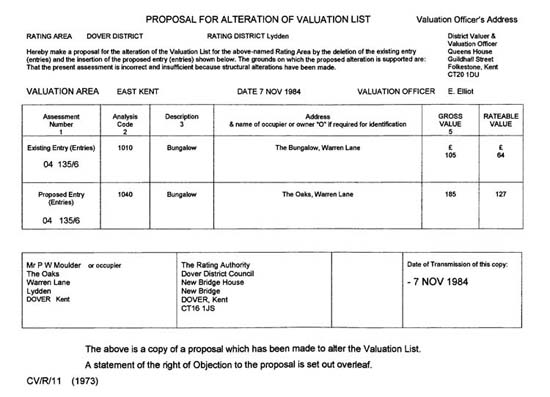

After I had finished the works of improvement and repair to my bungalow an Officer from the District Valuers Office carried out a close inspection of it on 24th October 1984 in order to reassess the domestic rateable value. During this inspection the officer had in his possession a copy of the original plans of the bungalow to which he referred whilst accurately measuring the renovated property. He concluded that the measurements and construction of the renovated bungalow remained the same and subsequently reassessed the domestic rateable value due to the improvements.

The bungalow’s assessment reference number remained the same when the valuation increased on 7th November 1984. The lawful residential use was not challenged at this time and in his report the officer refers only to works of renovation carried out to the lawfully existing bungalow. NO mention, whatsoever, is made of ‘the erection of a new dwelling’, which the Council falsely claimed.

Throughout the time the bungalow was empty, prior to my purchase, it remained weatherproof with intact windows, walls and roof, thereby retaining the essential characteristics of a dwelling. When I viewed the bungalow in April 1984 the estate agent had to provide door keys because the property was locked and secured. I moved into the bungalow in June 1984.

Whilst empty the property had been targeted by vandals thus the owner, Miss Dickinson, took the precaution of boarding the windows up to secure the property and guard against vandalism. She also employed her neighbour to clear the overgrown garden, prior to instructing the estate agent to sell the bungalow. Miss Dickinson’s actions were highly indicative of her intention at that time, which was to preserve the building and not to abandon its residential use.

Therefore the residential use could lawfully be resumed without planning permission.

Prior to purchase my solicitor carried out all the usual searches and the Enquiries of District Councils Form was completed, signed and dated 21 May 1984 by Lesley Cumberland, Director of Legal and Administrative Services of Dover District Council.

All references to the Public Health Act, Town & Country Planning Act and General Development Order, relating to permitted-development, were answered in the affirmative and the existing, long-standing residential use was not challenged, thus the Council’s legal department ratified the current lawful residential use.

If the Council had reservations about the residential status of the property then this was the time to declare them. My Solicitor had put them on notice that I intended purchasing the property as a residence.

When I moved into the bungalow it already benefited from a bathroom and kitchen and included the previous owners furniture and curtains. In addition there were packets and tins of food in the cupboards along with magazines and newspapers, all indicating fairly recent domestic use.

Further evidence that the residential use had not been abandoned is contained in a letter from Lesley Cumberland, Director of Legal and Administrative Services to my solicitor, dated 8th October 1984, which stated:

“…I have conferred with the Director of Planning on the alleged statement that the residential use of the site may have ended, and I can confirm that the Council are not saying that the residential user rights have been abandoned, only that the operation carried out on site is, as a matter of fact and degree, a building operation and thereby constitutes development requiring planning permission…”

Signed…

LESLEY CUMBERLAND

Further conclusive evidence that the residential use had not been abandoned is contained within a Planning Inspectorate letter. The Planning Inspector, Richard W. Pratt, stated:

“A bungalow was built on the site in about 1928, and remained in use as a dwelling house up to the time of the appellant’s acquisition of the land in 1984……

I accept that, at that time, the residential use of the building would have been lawful, because it pre-dated the Appointed Day, 1 July 1948″.

When I made a complaint against the Council an investigation was carried out by their own senior Professional Standards Investigator. His report made direct reference to the question of abandonment when he stated the following:

- 3.6 There is independent evidence that the bungalow was used for residential purposes from 1934 to the summer of 1982…

- 3.32 Taking into account the Planning Inspectors findings in November 2000, the Head of Legal Services advice to the complainant’s solicitor in her letter of 8th October 1984, the evidence provided by the next door neighbour and the undisputed evidence that between June 25th 1984 and 31st July 1989 the complainant and his family lived at the Oaks, it is my view that there is a record of residential use of the site from 1928 to 31st July 1989.

- 6.22 It is my view based on the contemporary evidence of neighbours, the finding of the planning inspector in November 2000 and the statement made by the Director of Planning and Administrative Services in her letter of 8th October 1984, that at the time residential user rights had not been abandoned and indeed existed.

There is irrefutable evidence therefore, that the residential use of the bungalow had not been abandoned.

Despite the Council’s own legal department being fully aware that the residential use had NOT been abandoned, they erroneously pursued a path of action stating that it HAD been abandoned. This indicates reckless pursuit and malice aforethought, making the subsequent demolition of my home an act of criminal damage.

Copied below is legal advice about what constitutes a dwelling house and the related concept of abandonment. It is important to note that this is an internal memorandum from Dover Council’s Head of Legal Services to their planning department.

It concerns a rural property known as ‘Windy Ridge’, Preston Hill, Wingham, a bungalow that had been destroyed by fire in August 1977 and which remained an uninhabitable ruin for 21 years before an application was made for a Certificate of Lawful Use.

MEMORANDUM

From: HEAD OF LEGAL SERVICES

To: Director of Planning and Technical Services

(Originator) Ian Ginbey – Ext: 2328

Attn: Tim Flisher

Subject: WINDY RIDGE, PRESTON HILL, WINGHAM

Your ref: TJF/EC/DOV/97/0912

My ref:-L/IG/PLAN 1(W)

Date: 7 July 1998

Thank you for your memorandum of 29 June.

I note from the letter which you have received from the applicant’s agent that the application is now restricted to the “chalet” which is essentially what was agreed at last month’s site meeting. My recollection of that meeting is that it was also agreed that a structure, such as the “chalet”, is capable of being described as a “dwelling-house” and reference was made, in this respect, to the Gravesham case. This is also confirmed by the agent.

I would only add that you should have regard to the related concept of Abandonment in the context of the application. In most cases, these two concepts are fused; that is, facts that point to abandonment will also point to the conclusion that the building is not a dwelling house. It follows that in the instant case the applicants should evidence that the use of the “chalet” as a dwelling-house has not been abandoned in order to gain the benefit of a Certificate of Lawfulness of Existing Use pursuant to Section 191 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990.

I recall that the submitted evidence is a little vague in this respect with only one statement making reference to Miss Maxted’s occupation of the “chalet” (although it is possible that some of the evidence has been given on the premise that the bungalow and the “chalet” are one and the same). It is, of course, a matter for you to determine as a matter of fact and degree and you no doubt formed an opinion at the site meeting. Certainly, there appeared to be some evidence of residential occupation.

Notwithstanding the above, I should add for the sake of completeness that there obviously can be cases where even though a dwelling-house use has been abandoned, the building may still be regarded as constituting a dwelling-house. In such cases, operations could be undertaken to the building, but clearly it could not be used as a dwelling house without the grant of planning permission.

Contrariwise, I suppose it is just conceivably possible to argue that, although a building was such a ruin that it could not be considered a dwelling house, the use as a dwelling house had never been abandoned.

Ian D. Ginbey (Assistant Solicitor)

For Head of Legal Services (JWH)

‘Windy Ridge’ is just one example of the extreme inconsistency that is prevalent in Dover District Council’s decision making. There are many more.